"There are too many nonprofits and they need to consolidate..." is one of my least favorite sentiments in the nonprofit space.

One reason is that it's an untethered relative. An absolute statement suggesting that a value should increase or decrease without specifying by how much.

If there are too many nonprofits, by how many? At what tipping point would you say we actually have too few?

While I don't know the optimal quantity of nonprofits, I've never felt like there are too many and I believe that consolidation would be a mistake.

I created a dataset with simulated revenue numbers for forty nonprofit organizations to help me illustrate this thought experiment.

An illustration

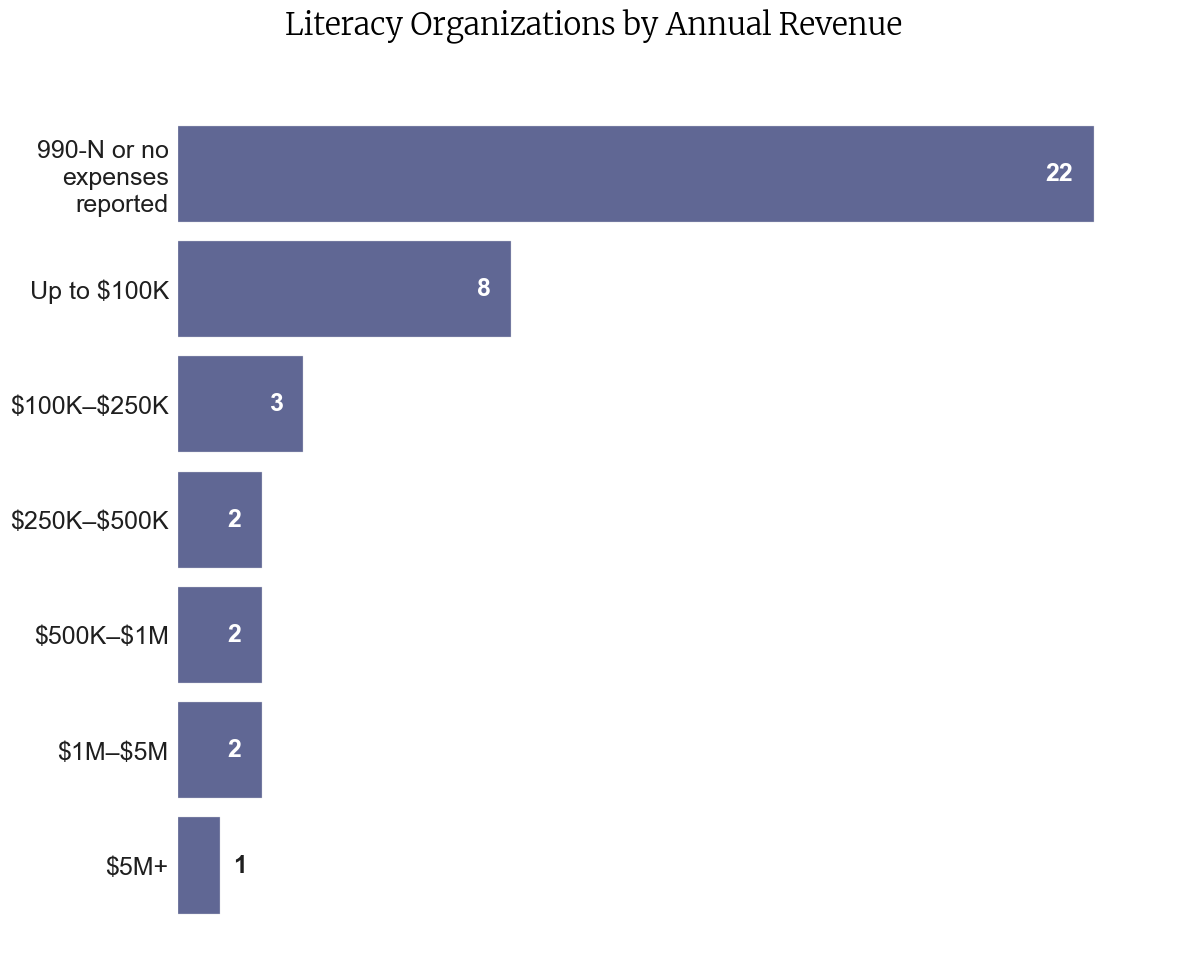

Let's say that a community of 500,000 people has 40 organizations dedicated to literacy programs. If the size of these nonprofits is in line with national averages, then they are probably distributed like this.

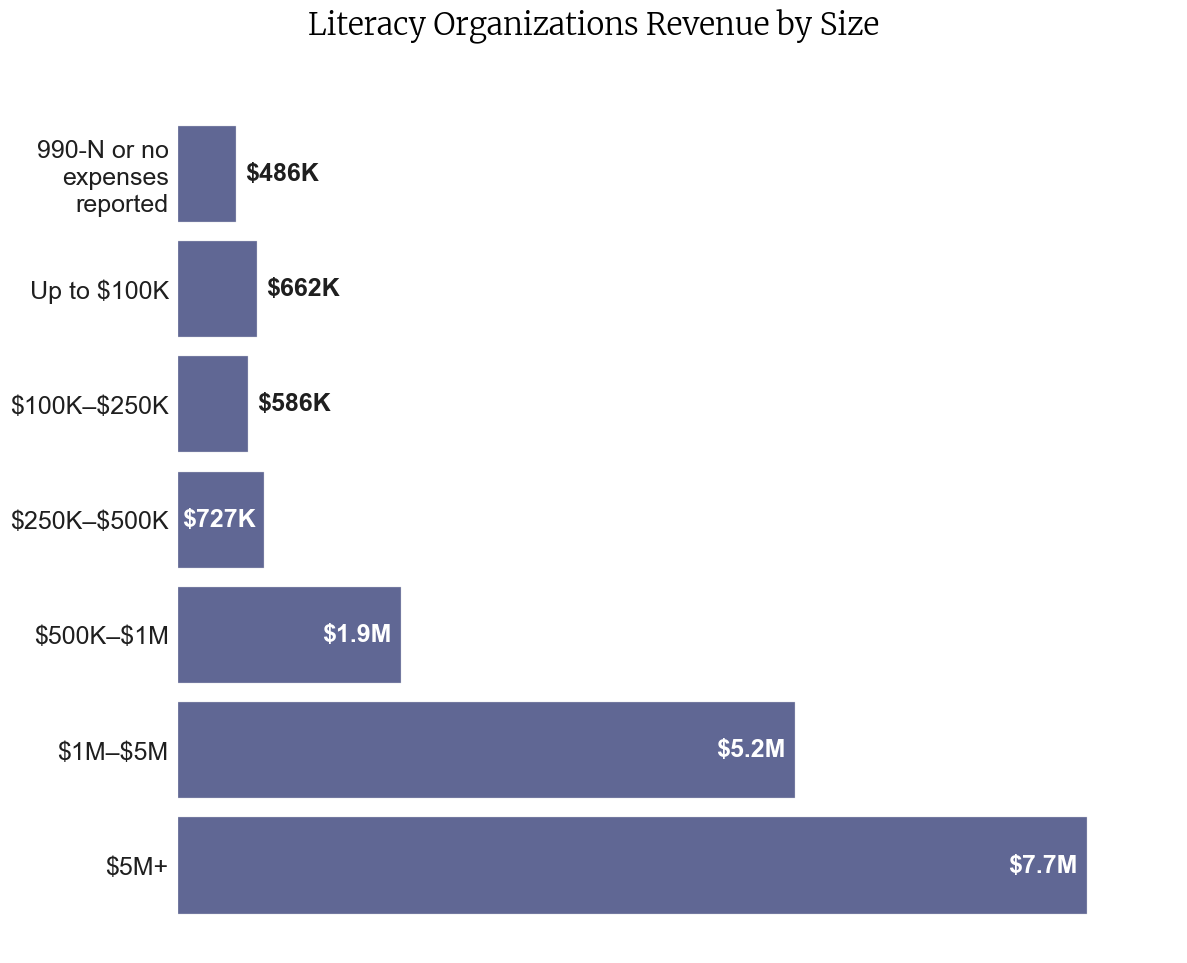

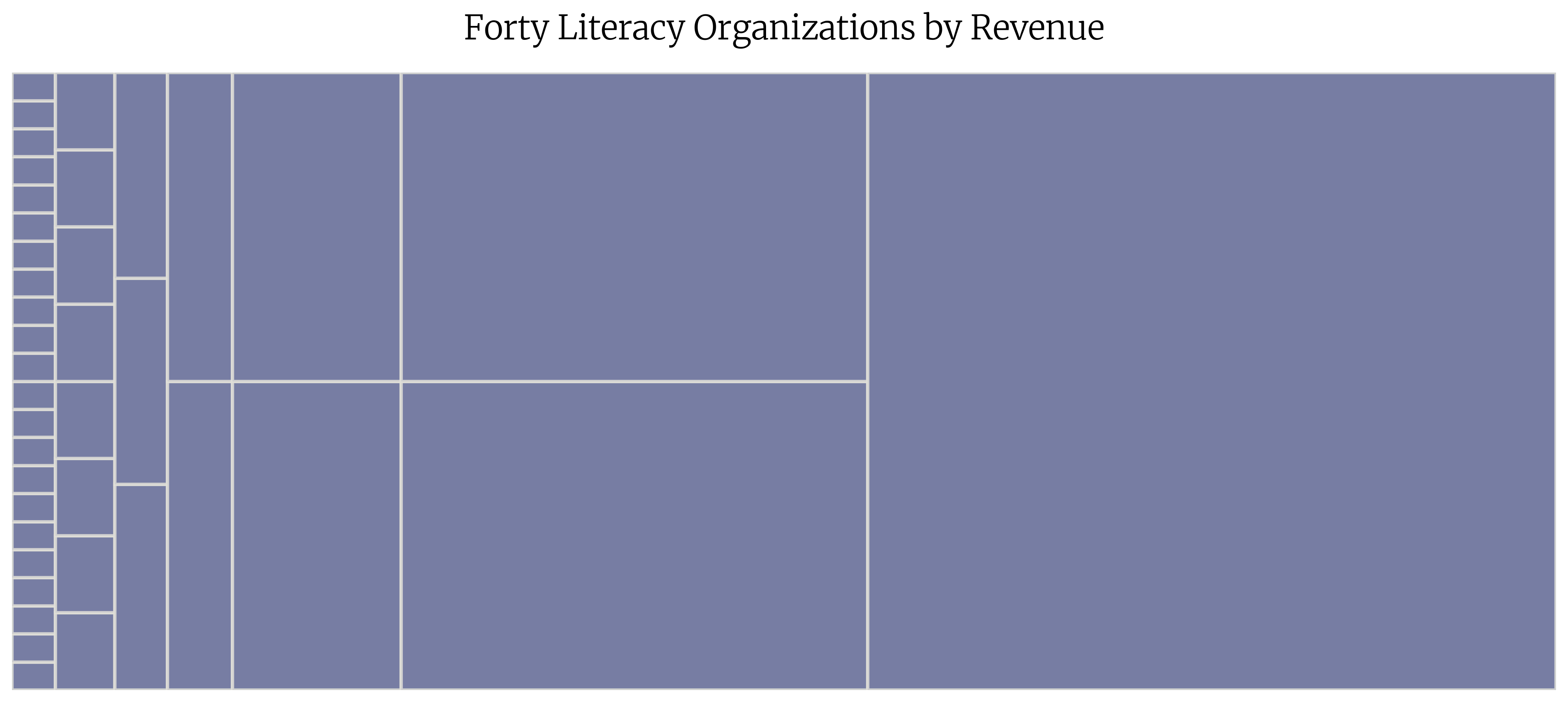

If we sum the revenue generated by each of these categories, you can get a sense of which organizations receive revenue.

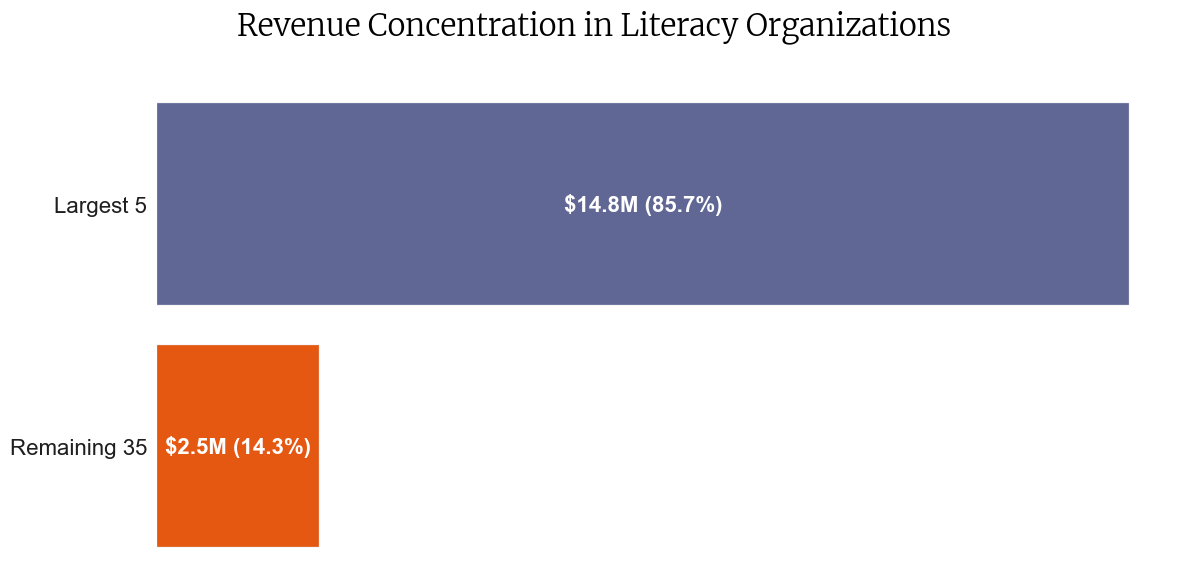

Even though there are 40 organizations devoted to literacy, the largest five receive 85% of the revenue. When people say "there are too many nonprofits", I think they envision this:

But they should actually picture this:

When we consider consolidation, the largest organizations are most likely to absorb the smaller ones. If we assume the five largest are the best suited (track record, leadership, infrastructure, etc.), then we can get a sense of the opportunity consolidation creates.

This imaginary literacy sector brings in $17.2 million dollars. By eliminating the smallest 35 organizations, this, in theory, creates $2.5 million dollars of opportunity to be redistributed to the larger organizations.

With this framing, I'll rattle off a few reasons why I don't think consolidation makes sense.

It won't save money

Proponents of consolidation (let's call them consolidationists) suggest it will make the sector more efficient and I disagree. Organizations with less than $50,000 in revenue are not wasting money (relative to their peers), for the very simple reason that they barely have any money to waste. Even if they wasted 100% of their money, it would still be easier to find $486K of waste in the largest five nonprofits than it would be to pull out a microscope and analyze the line items of 22 organizations that can't afford to pay a single staff member.

It puts revenue for literacy at risk

Organizations bringing in less than $100k a year are usually not receiving corporate money or grants from foundations. Instead, their revenue comes from friends and family. This category of donor doesn't give to the abstract cause of "literacy"; they give because someone they love was relentlessly passionate about a cause. Passion leads to revenue.

The majority of the $2.5 million in revenue brought in from the smallest 35 organizations is not literacy money–it's friends and family money.

Consolidation assumes that this would be revenue neutral for the sector. Are we convinced that the largest five organizations will be able to retain 100% of this friends and family money after absorption? I don't think that's a reasonable assumption.

It eliminates one of the causes greatest assets

When we say that we'd be better off with five literacy organizations instead of forty, let's not forget that we're also saying we'd be better off with five executive directors instead of forty. More bluntly, we're suggesting that thirty-five people go home.

Consider this (made up) news release:

"In partnership with the community foundation, we've identified 35 leaders who offered to raise 2.5 million dollars from their family and friends for literacy programs. Nearly all agreed to work as volunteers, and the handful that do receive a salary will work for half of what they could make in the private sector."

This news would be widely celebrated in any community because its a remarkable asset. Volunteers that raise millions of dollars!? How can we find more of these people?

The idea that a community would be better off with 35 fewer leaders committed to a cause will always befuddle me.

Maybe you think these executive directors will find roles in the larger organizations that absorb them, but the math doesn't work. If the nonprofit they lead today can't afford to pay them, hiring them after consolidation will lead to more overhead–not less. The only way consolidation works is if these super-volunteers hang up their hats.

Wrapping this up with a bow

I believe consolidation would reduce revenue for the sector, not create new efficiencies, and alienate dozens of the community's richest assets. And I have even more reasons... (it destroys the nonprofit minor leagues, stifles innovation, etc.)

But here's the real reason I don't want to talk about consolidation anymore:

Because its never going to happen.

Let's say that community leaders magically come together and agree (lol) on the five organizations that should absorb the other thirty-five (super lol). Let's say that when these community leaders approach the thirty-five executive directors and suggest that the community would be better off if they quit, all thirty-five executive directors agree to go home.

When this magical consolidation happens and the community finally gets what it needed–five organizations committed to literacy, what would happen next?

Within three years, thirty five new literacy organizations would be created.

Why?

BECAUSE THIS IS A FREE COUNTRY.

For all of America's faults, we are entrepreneurs. Pioneers. Creators. Innovators. People brimming with delusion who see the world as it is and think to themselves, "I can make it better."

The bar for starting a nonprofit is so low. Literally anyone can do it. Consolidation only makes sense if you can stop the creation of new nonprofits.

Consolidation goes against the grain

If we push consolidation to its logical end, we arrive at government control of the entire philanthropic sector. Whether you like that idea or abhor it, that's not how the system was designed.

Another word for nonprofit is NGO: Non-government organization. De-centralization is baked into the design. I think its a feature; not a bug. Regardless of how you feel about it, we can't change it.

So let's go with the grain instead of against it.

Embrace the madness. Join me on the wild side–the side of the greedy fragmentationalists.

Who, when asked, "how many nonprofits would be enough?" reply:

Just a few more.

Until next week,

Ted